Revolution Within The Form - It Can Happen Here

America's elites know better than to formally abolish the constitution. So did Julius Caesar.

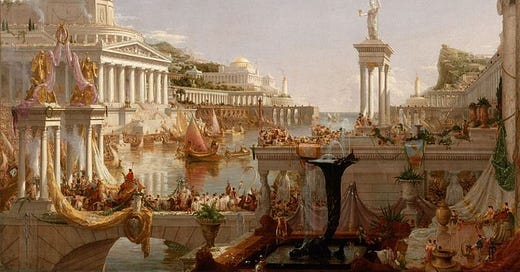

When did the Roman Republic end?

Modern historians usually give a fairly precise answer: in 27 BC, when Octavian was granted the title of “Augustus” and became the first full-fledged Roman Emperor. While some might point to 49 BC, when Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon, or 44 BC, when he was made Dictator for Life, as the more important date, they all pretty-much agree that sometime in the late first century BC, the Republic was destroyed and a new, very different form of government was raised on its carcass.

And their ability to agree that this happened does not depend on their subjective opinions regarding the desirability of the transformation. Both those who look up to the Caesars for restoring peace and civic order to a dysfunctional and war-torn realm, and those who admire Brutus and Cassius for slaughtering a tyrant, alike credit Julius Caesar and his nephew Augustus with the destruction of one system of government and the foundation of a new, radically different one.

Curiously enough, almost nobody who actually lived through those events saw it that way.

There were a few outliers – Brutus and Cassius, of course, and Cato the Younger, who committed suicide rather than live under Caesar’s authority. But the overwhelming majority of Senators, who freely gave Augustus all the power he wanted rather than let their country slide back into civil war? The poets like Horace and Virgil, who eulogized both Julius and Augustus as heaven-sent defenders of the ancient Roman constitution? The pairs of young aristocrats whom the new regime, year after year, kept honoring with the consulship – an office which, though stripped of actual power, was still a gateway to immense wealth and prestige?

As far as these people were concerned, the Republic had never been stronger.

Senators, consuls, tribunes, praetors, quaestors, aediles – all continued to be elected in due order. In theory, their powers were the same as before. In practice, everything important was decided by the emperor.

But great care was taken to preserve the external forms of the Republic. The Romans had a word for a monarch, the good old Latin Rex, which no emperor, however corrupt, dissolute, or hubristic, ever dared use. Imperator, Princeps, Caesar Augustus – each of these titles, grandiose as they may sound to the modern ear, started out as a euphemism for “king.”

Rome had undergone a revolution within the form. The old organs of government – senate, consuls, etc. – were still present. But they had become vestigial organs, like the wings of an ostrich, mere holdovers from an earlier stage in the state’s evolution.

Machiavelli, steeped in the rough-and-tumble politics of Renaissance Italy, understood this concept quite well:

“He who desires or attempts to reform the government of a state, and wishes to have it accepted and capable of maintaining itself to the satisfaction of everybody, must at least retain the semblance of the old forms; so that it may seem to the people that there has been no change in the institutions, even though in fact they are entirely different from the old ones. For the great majority of mankind are satisfied with appearances, as though they were realities, and are often even more influenced by the things that seem than by those that are.” (Discourses on Livy, XXV).

Look beyond Rome, and it isn’t hard to find more examples of what Machiavelli is describing. The transition can go away from monarchical rule as well as towards it – Europe in 2021 still has seven reigning kings and queens, not one of whom actually rules. Perhaps the simplest way to think about revolution within the form is that it’s what happened between Elizabeth I and Elizabeth II. On paper, their powers are the same. In practice, a lot of things have changed.

Nor did the changes only involve the Crown. Britain is actually very well stocked with vestigial organs of government: the prime minister is not only outranked by the Queen and her family, but also by a whole bevy of non-royal ‘Great Officers of State’ like the Lord Chancellor, the Lord Great Chamberlain, and the Lord Privy Seal, each of whom once wielded immense power. And then there are the peers, and the privy council, and the Lords Spiritual, and the Earl Marshall… well, you get the point.

Britain and Rome – monarchy to democracy and republic to monarchy – are hardly the only games in town. Japan, for example, once did a revolution within the form from monarchy to monarchy. The current imperial dynasty dates to sometime before the seventh century, yet for about half of its history – between the years 1192 and 1867, to be exact – all real power belonged to a line of military officers called shoguns, whose full title roughly translates as “High Commander of the Defense Force Against the Barbarians.”

In theory, the shogun was an army officer appointed by the emperor to wield extraordinary powers during a time of crisis; in practice, he was an absolute monarch in his own right. Nevertheless, in keeping with its ad hoc origin, the administration through which the shoguns ruled was called the “Tent Government.” The emperor, meanwhile, presided over his own court and his own retinue of officials. Unlike the Tent Government, these people didn’t exercise any political power, though presumably they had a nicer living quarters.

At a certain point, the divergence between formal and actual power ceases to fool anybody, but continues to persist as a quaint turn of speech – the way, for example, that British lawyers still talk as if the Queen had personally initiated every prosecution in the British courts.

But what interested Machiavelli was the period when the illusion was fresh, when it could still “seem to the people that there has been no change in the institutions, even though in fact they are entirely different from the old ones.”

Britain is no longer in that phase… but the United States is.

During the middle decades of the twentieth century, the United States underwent a slow but thorough transition away from democracy and towards oligarchy, away from a system where the greatest share of political power was wielded by elected representative bodies, and toward one where nearly all power is wielded by wealthy, unaccountable professionals ensconced in various elitist institutions.

Obviously, nobody respectable has admitted this. Officially, democracy is still important enough that we had to invade Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, etc. in order to spread it. But if you examine America’s organs of government, and separate the vestigial organs from the functioning ones, you’ll see that the democratic organs are vestigial, and the oligarchic organs are functional.

It shouldn’t be hard to identify the vestigial organs. Let’s start with the White House – the most democratic of our offices, since it’s the only one that gets chosen in an election which most people still care about.

Donald Trump generally gets credit for being the most bizarre and erratic president in at least a century. Naturally, one would be curious about what happened when the Donald became the ‘Leader of the Free World,’ and what happened when he went back to being an ordinary citizen four years later.

Well, the day after Trump’s win, back in 2016, a bunch of college professors made the news by allowing their terrified students to bring puppies into the classroom to sooth their fears for the future. And shortly after Trump’s loss in 2020, a mob of terrified Trump supporters, driven berserk by their fears for the future, broke into the Capitol building and carried off Nancy Pelosi’s lectern.

Other than that? Not much. All throughout the Trump years, the border remained mostly open; while ICE detained and deported illegal aliens under pretty-much the same conditions as during the Obama years, this process remained too slow and sporadic to really matter. The US was involved in the same Middle Eastern wars when Trump left office as when he arrived. Nothing decisive had been done about the collapse of the manufacturing sector. And so forth.

As in the year before Trump took office, so in the year after he left, the Supreme Court is pursuing a pro-business but socially liberal agenda. Even with six Republicans, including three Trump appointees, the Court couldn’t get enough votes to even hear the case of that florist in Washington State who is about to lose everything she owns for refusing to service same-sex weddings.

The various administrative agencies that make up the “Executive Branch” pretty much ignored Trump and his cabinet. Do you remember Jeff Sessions or Rick Perry or Ben Carson or Betsy DeVos? Can you think of anything their respective departments did, or refrained from doing, on account of their leadership? Do you think that day-to-day life in those departments has changed now that they’re gone?

If your answer was ‘No,’ then that’s pretty good evidence that the cabinet is just as passive as the presidency. Cabinet members and other “political appointees” have practically no control over the agencies they supposedly lead. They cannot hire or fire the people who work for them. And these lower bureaucrats – the “permanent civil service” – are, for the most part, dyed-in-the-wool leftists who aren’t shy about flaunting their independence from the elected portion of the government, whenever the latter is in Republican hands. Which is why people who worked for the Trump Justice Department got to go to so many racial struggle sessions. And why the immigration laws continued to go unenforced.

Even in areas where it seems like the President is the sole or main decider – foreign policy and judicial nominations – he still often manages to be irrelevant in practice. With regard to foreign policy, all recent presidents have been pliable men who allowed their advisers in the Pentagon and State Department to herd them along the path of least resistance, which is why Obama, after winning office by running against Bush’s foreign policies, proceeded to imitate them practically to the letter, and why Trump did the same thing with Obama’s policies.

As for judicial appointments, the constraint is that, usually, the only nominees who can get through the Senate are the slippery kind with few or no discernible principles, so despite the occasional outlier like Clarence Thomas, even judges put on the bench by Republicans will have the same average beliefs as the people at Harvard and the American Bar Association. And it doesn’t help that power clings to itself, and that, once in power, judges frequently migrate toward ideologies that invite them to see their power as unlimited – i.e. toward leftist ideologies.

Congress is even more passive than the presidency. Changing the Constitution used to require a two-thirds vote of each house of Congress; now it requires a Supreme Court decision. Going to war used to require the approval of Congress; now it doesn’t. Apart from judges, the officials that Congress has to confirm wield less power than the officials that it doesn’t have to confirm. Money is created by the Federal Reserve, which reports to no one. And the legislative role of Congress has been almost entirely absorbed by the administrative state.

In theory, Congress’ powers are immense. In practice, it is very hard to get anything through Congress. As a result, very few of the important decisions which the government has made over the last half-century have been made by Congress.

Jury trials are another vestigial organ of democratic government. In theory, the United States has trial by jury; in practice, it has trial by plea bargain.

If these (along with their counterparts at the state and local level) are the vestigial organs, then what are the functional organs? Who actually decides what the law is?

Well, unlike America’s external empire, which is governed by chance, the internal empire at least has a semblance of law. Its lawmaking process is as follows: the Supreme Court can do anything. Congress can do whatever it wants, within the boundaries set by the Supreme Court. The administrative agencies can do whatever they want, within the boundaries set by Congress and the courts.

Congress, occupying the middle position, is by far the least important of the three – it has neither the omnipotence and finality of the Supreme Court, nor the omnipresence and immediacy of the agencies. The nine Supreme Court Justices, on the other hand, collectively hold the imperium maium. This is a fancy way of saying that the law is whatever the Court says it is, and that the Court’s power is not in any way limited by the other branches of government.

(In regimes where the imperium maium is held by a single man, we all act horrified and call him a “dictator.” The nonchalant attitude of most Americans toward a system where the same role is held by a committee of nine would have baffled the Founders).

According to state ideology, the Court rules by “interpreting” the Constitution. That decisions like the banning of school prayer or the legalization of abortion were made by interpreting the Constitution is one of those official fictions that a child can see through, but which adults do their best to believe in order to show their loyalty to the regime, as in “Oceania has always been at war with Eastasia.”

The phrase “final interpreter of the constitution,” is a euphemism for “top legislature” in much the same way that “emperor” was a euphemism for “king.” Augustus called a monarchy a republic. Our own ruling class calls an oligarchy a republic.

Now, it was a stroke of Machiavellian genius, in the sense of retaining “the semblance of the old forms,” that rather than create a new body by which to govern, the new ruling class repurposed an old one. That the United States should have a Supreme Court is not a new idea; that this court should have jurisdiction over constitutional cases is not a new idea; nonetheless, the role and function of judges in the new system is completely different than their role and function in the old one.

In traditional Anglo-American politics, the duty of judges was to enforce pre-existing laws against the litigants in the case that they had just heard. Obviously, disputes over the correct meaning of the law would arise from time to time, and laws had to be adapted to situations not anticipated by their drafters (do the police need a warrant to tap a telegraph line?) Still, nearly everyone involved viewed their task as enforcing and regularizing the laws, with as little innovation as was necessary to make them enforceable – not replacing bad, old laws with good, new ones. In short, the whole legal profession was geared towards ensuring that the laws had a consistent and uniform meaning across space and time.

While judicial review is almost as old as the constitution itself, it was also, until fairly recently, a conservative force only. To give two of the most famous examples, in 1803, John Marshall ruled that Congress can’t add to the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction; a century later, Rufus Pekham ruled that states can’t make laws limiting workers’ hours in a bakery. Both decisions, while (justly) controversial, were merely exercising a de facto veto power over new and controversial laws. On the other hand, using the judiciary to initiate changes and reforms – and thereby purging the lawmaking process of the pesky interference of voters – is an innovation of the post-New Deal Left.

In theory, Congress and the President have ways to reign in abuses of judicial power – impeachment, the exceptions clause, and adding new seats to the Supreme Court, to name a few. In practice, none of those things have even been seriously discussed since the 1930s. Right now, the Court’s imperium maium is secure.

But the system is big, and the imperium maium is only one piece of it. Nine people can’t even see most of what the government is doing, let alone care about it, let alone control it. Most of the rules that effect how ordinary Americans live their daily lives are made by administrative agencies, operating under broadly written congressional mandates, drafted by lobbyists and usually enacted with little or no debate.

Which drugs is your doctor allowed to prescribe for you, and when must he warn you about potential adverse effects? How high and how fast can commercial delivery drones fly? What shall be the interest rates on federal student loans, and should those loans accrue interest while the borrower is still in college? Can a hog farmer operate his own on-site smokehouse? To whom may a dairyman sell raw milk? What will happen to an elementary school if its students do poorly on federal standardized tests? Can the school wriggle out of these consequences if enough of its students are diagnosed with and/or medicated for ADHD?

Usually, a decision like this is made by majority vote of a small panel, perhaps with just three or five members, in some regulatory agency. Who are these people? How did they get their jobs? Who the hell knows?

Oftentimes, the people who are most affected by the decision do know what’s going on, and they’ll petition America’s democratic institutions, like Congress and the White House, to wake up and do something. And in theory, all these regulators could have their decisions overturned, or even be dismissed from office, as a result of such petitions.

In practice? None of these controversies, on its own, will get nearly enough people hopped up to overcome congressional inertia. Voters and elected representatives might as well be the Queen of England for all the influence that they have in their country’s government.

Thus goes oligarchy in America. One set of institutions holds formal power; another, very different set holds actual power. Under the constitution as originally written, the first set is more than strong enough to overcome the second. But it’s stocked with people who, as a matter of ideology, or habit, or pragmatism, or whatever, never contemplate doing so. And the voters, having fallen for the Machiavellian sleight-of-hand, are content with the appearance of democracy rather than the actual thing.

Like all regimes, oligarchy in America won’t last forever. No matter what facet of American life you look at, the evidence of decline is unmistakable. Perhaps, when it falls, the oligarchy will be replaced by something better. The slow collapse of the global fossil-fueled economy might break the US into smaller pieces, and toughen up their inhabitants into the sort of men we had during colonial times, making genuine democracy possible again. Though the system could also weather the crisis by undergoing another revolution within the form, perhaps ending up with a shogun-style de facto monarchy masquerading as an ad hoc crisis response team. At this point, it’s too early to say.

Whatever form the new regime takes, one thing is for sure – its historians will not shy away from discussing the dedemocratization of twentieth century America. Propaganda never outlasts the regime that created it, and no one licks a dead man’s boots. While the scholars of the twenty-sixth century may have lively debates about the desirability of OSHA, or Planned Parenthood v. Casey, or what have you, none of them will pretend that these things existed within a functioning democracy, any more than our own historians pretend that the office of Roman Emperor existed within a functioning republic.

Meanwhile, if America’s remaining patriots are going to salvage something good out of the situation, we will need to wake up from the propaganda that seduces us – from the complementary lies of the Left and the Right – from the claim that the changes of the last century are mostly good, and also from the claim that, while many these changes are bad, the old system of checks and balances is still mostly intact, and we can turn the situation around by voting for Republicans.

As unpleasant as it may be to admit it, this much is clear: the vestigial organs of government are not going to be reactivated. The ostrich is not going to spread its wings and fly.

At this point, collapse is not avoidable. Nor should we want to avoid it. There is no honor in bowing down to the plutocratic oligarchy that has been erected on the carcass of the old republic. Our present task is to detach ourselves from the system, work toward spiritual, intellectual, and material independence, look out for the welfare of our families and whatever small communities we happen to belong to, and do our best to outlast our enemies.